You may have been advised in the past that making a range offer during negotiations is a bad move. However, some new research from Columbia Business School proves differently and that range offers are beneficial.

“For years, we taught students to avoid making range offers in negotiations, assuming that counterparts receiving those offers would have selective attention, hearing only the end of the range that was attractive to them,” said Daniel Ames, co-author of the research and the Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao Professor of Business at Columbia Business School. “Our results surprised us, up-ending how we teach the topic. We can’t say that range offers work 100 percent of the time, but they definitely deserve a place in the negotiator’s toolkit.”

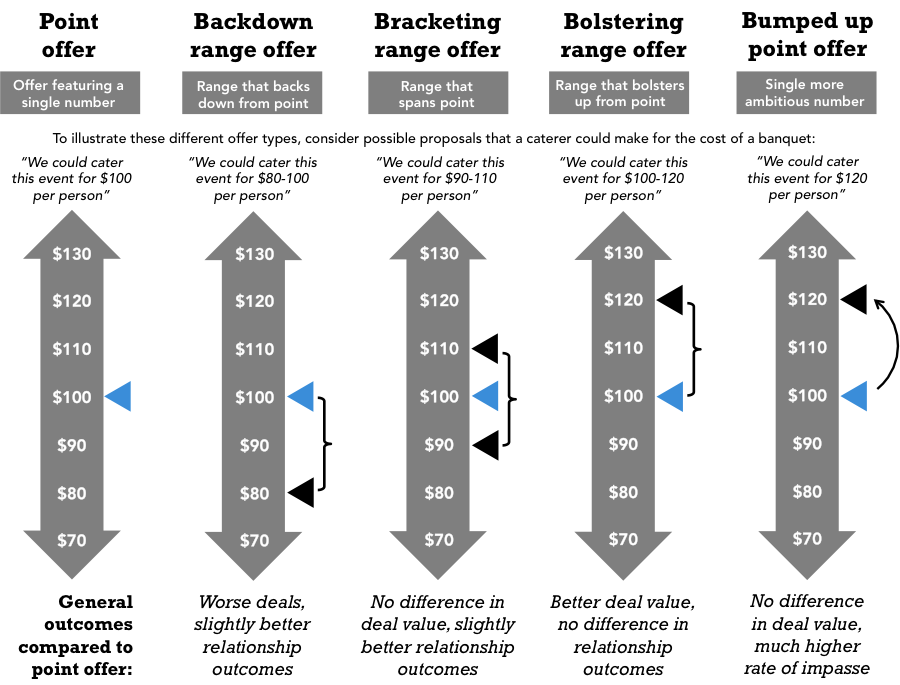

For the research, Ames and co-author Malia Mason, the Gantcher Associate Professor of Business at Columbia Business School, conducted a series of studies to understand people’s reactions to negotiators making a variety of different offers. Single-number point offers, such as asking for a 15 percent discount, were compared with three different kinds of range offers. Here’s what they found.

Bolstering Range Offers

These start with the point and stretch in an even more ambitious direction, like asking for a “15 percent to 20 percent” discount instead of just “15 percent.” Most negotiation experts say this strategy is doomed because the bargaining counterpart would hear only the 15 percent end of the range. Ames and Mason found that Bolstering Range Offers frequently led to better settlements for the offer-makers without harming the relationship with the other party.

Bracketing Range Offers

These span the point, such as asking for “13 percent to 17 percent” instead of “15 percent.” Experts in the past would likely have said this strategy was sure to lose value. Ames and Mason found that negotiators using Bracketing Range Offers didn’t reach worse deals than those using point offers, but they frequently experienced relationship benefits, such as being seen as more flexible.

Backdown Range Offers

These start with the point and then offer a more accommodating value, like asking for “12 percent to 15 percent” instead of “15 percent.” In this instance, Ames and Mason’s research fell in line with prior conventional wisdom. Those using Backdown Range Offers ended up with less value than those using point offers, but didn’t see more relational benefits than Bracketing Range Offers.

“While negotiation experts have been advising against range offers for a long time, many people use them,” Mason said. “A good share of the time, people use backdown range offers, and our work suggests that’s unwise. But many people use bracketing or bolstering range offers, and our research shows that they’re onto something. Those range offers can draw out more accommodating responses from a counterpart.”

(Text and image: Columbia Business School)